Customer 360 and Data Mesh: friends or enemies?

Data Mesh is completely changing the perspective on how we look at data inside a company. Read what is Data Mesh and how it works.

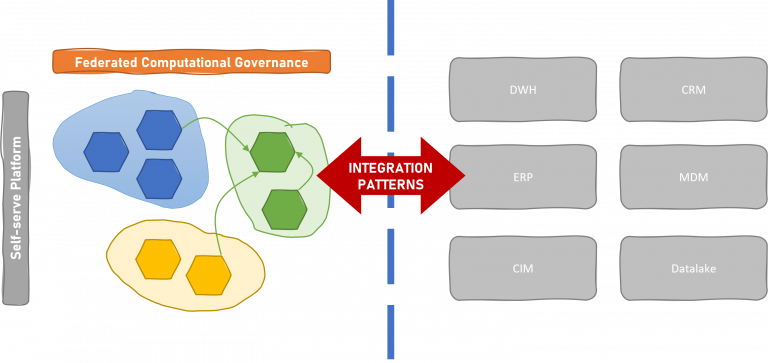

Integration patterns between operational and analytical monoliths with a data mesh and some use cases.

With the advent of data mesh as a sociotechnical paradigm to decentralize data ownership and make data-driven companies scale out fast, many businesses face organizational and technical issues adopting data mesh for several reasons.

This article focuses on the technical issues of a company that is in the stage of breaking data monoliths to enable inbound and outbound integration with the data mesh. I am going to discuss integration patterns that can address several organizational issues to achieve necessary tradeoffs among the involved stakeholders of a data mesh initiative.

A data mesh makes sense most of all for huge enterprises. The bigger a company is, the clearer is where all ropes of the data value chain start experiencing too much tension to fit in the current organization.

Adopting data mesh is far from being a mere technological problem, instead, it is very clear that many issues occur in the organization of a company. This does not exclude that current technologies are real concerns and impediments to the adoption of the data mesh paradigm.

Anyhow, looking positively at the future of a data mesh initiative, after removing major roadblocks to communication and technical silos in the principal folds of the enterprise, and having built the foundation for a data mesh platform, we may allegedly think of working in bimodality for a long while. The need for innovation in fast-paced enterprises will bring vendors of technological monoliths to move closer to the new paradigm. This may change the landscape.

A new data mesh will live side by side with data monoliths for a long period.

Nowadays, on the one side, we may see growing new data products in the data mesh ecosystem leveraging the self-serve capabilities of the platform. On the other side, we may see data mesh adopters striving to integrate data from the several necessary silos (operational and analytical) that realistically still exist in any big enterprise.

Domain Driven Design has been around for a while shaping microservice architectures through this paradigm in many companies. Data Mesh inherits and extends those concepts to the analytical plane embedding best practices from DevOps, product thinking, and system thinking. Here is an opportunity to close the gap between the needs for operational and analytical scenarios.

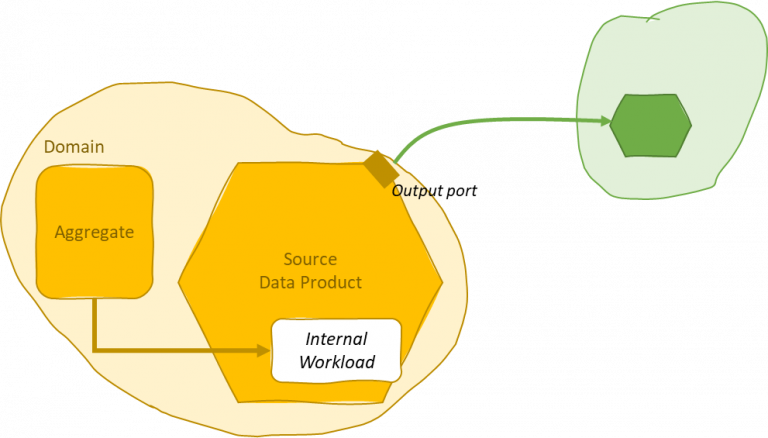

It should be encouraged to holistically see a source data product as a direct extension of DDD-ed entities. The same team working on microservices may also deal with analytical scenarios opening to data engineers, data scientists, and ML engineers.

The data mesh platform team should enable easy integration between analytical and operational planes by providing as many as possible out-of-the-box data integration services to be autonomously instantiated as part of the data product workloads by the domain.

A domain-driven microservice architecture can close the gap with the analytical plane.

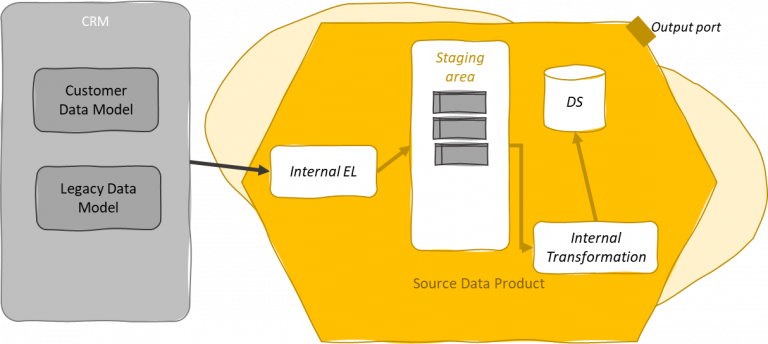

Big enterprises are not homogeneous, there are many silos of both operational and analytical natures, and many of the operational ones will never move realistically to a microservice architecture because of the complexity to remove technological silos some key business capabilities rely on. This is common for CRM and ERP legacy operational systems. They are typically closed systems that enable inbound integrations and restrict outbound ones. Often happens that analytical access to those monoliths is difficult in terms of data integration capabilities. The extraction of datasets from the silos is anyway required to enable analytical scenarios within the data mesh.

The data mesh platform either enables native integration with the data silos embedding extraction functionalities within the data product as internal workloads or should be open to customization and move the burden of the integration to the domain/data product team.

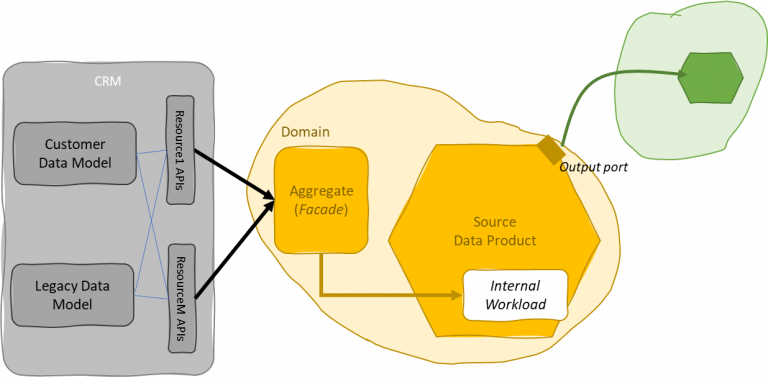

Internal workloads to extract data from operational silos. This is the case for a monolith that can extract a dataset representative of a DDD-ed aggregate.

Enabling native integration with an external operational silo would be the recommended way since those legacy systems usually can impact many domains and data products. This is particularly beneficial if the monolith enables the extraction of a dataset representative of the data model for the data product.

Such legacy systems are often generic and offer data modeling customization on top of a hyper-normalized legacy data model. Bulk extractions may or may not be able to address the customer’s data model so data products may need to deal with the underlying legacy normalized data model of the monolith. Further, it is not said that the customer’s data model fits into the domain-driven design given by the data mesh.

In this case, every data product should offload potentially many normalized datasets and combine them to get consistency with the bounded context. This might be repeated for every data product of each domain impacted by the monolith.

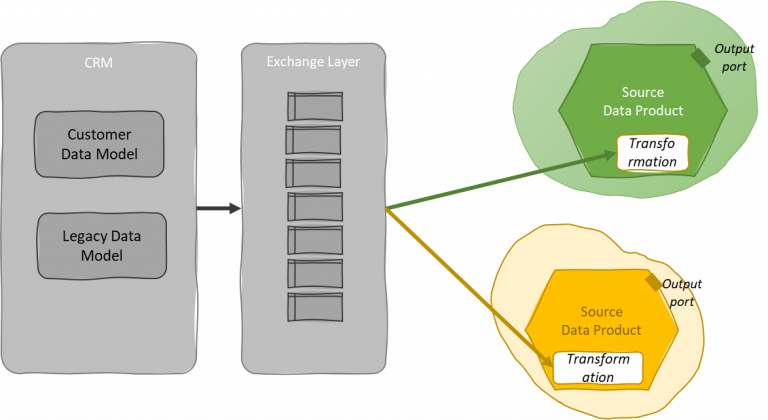

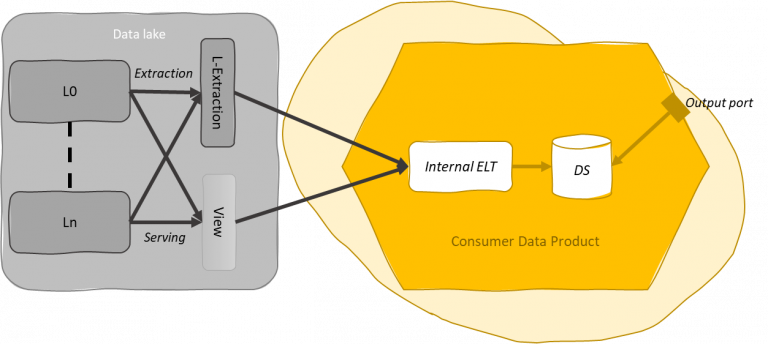

The previous case could be not the best compromise in the case where there is no easy direct integration with the external operational monolith and an intermediate exchange layer (sort of L0-only data lake) can be of help. This exchange layer might be operated by the same team of the legacy system keeping the responsibility of the quality of this data on the source side. The purpose of the exchange layer would be the minimization of the effort to offload data from the operational monolith in a shape that enables integration with the data mesh platform. The extraction of those data is governed by the data silos team and could be operated through traditional tools in their classical ecosystem. Later we will discuss better how to deal with analytical data monoliths (including such an exchange layer).

This connection is a weak point in the data mesh since the exchange layer tends to be nobody’s land, thus has to be considered the last chance. As usual, data ownership and organization can make a difference.

A final option I would consider to integrate operational silos into the data mesh platform is possible if there is a convergence between the data mesh platform and the operational platform like in the first described case.

The operational platform is the set of computational spaces that runs online workloads and is operated through best-of-breed DevOps practices and tools.

We may reflect the bounded context from an operational point of view into the operational platform by applying the strangler pattern. This may be particularly useful if the enterprise wants to get rid of the legacy system and applies to the case of internally developed application monoliths.

Depending on the case, a company may think to decompose the monolith by creating the interfaces first through the implementation of facades. After having domain-driven views of the monolith, the data mesh platform shall have the same integration opportunities already in place with the operational platform. Facades can be converted then into microservices replacing parts of the application monolith.

The strangler pattern enables domain-driven decomposition of application monoliths.

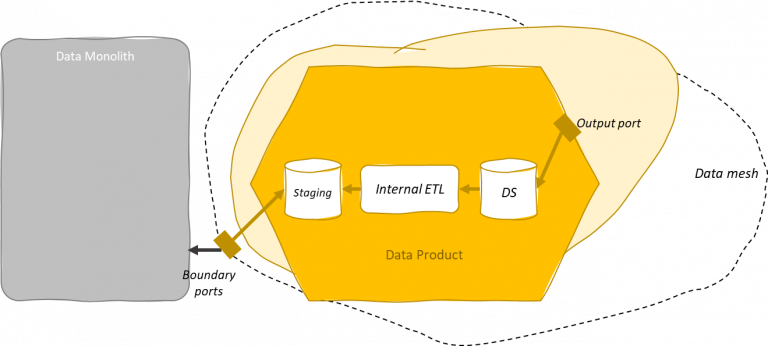

In the previous discussion, I analyzed some of the common cases where operational silos require integration with the data mesh platform and data products. In this section, I want to address the integration with existing analytical data monoliths that must be integrated with the data mesh. This may happen for several reasons: removing old monoliths or making the data mesh coexist with those monoliths.

Data monoliths can have several shapes. They may be in the form of custom data lakes or lakehouses, open source-based data platforms, legacy data platforms, DWH systems, etc. The recurring issue with those monoliths is the ease to bring data in and the challenge to extract data.

Building technical data products is not sensical. Thus, the purpose of this exercise is to allow the data mesh to leverage existing monoliths and enable analytical scenarios.

In this scenario, we are going to build both source or consumer data products depending on whether data from the silos reflects data sources (operational systems) that are not still accessible from the data mesh platform or analytical data assets that must be shaped into data products until they cannot be directly produced within the data mesh.

The data mesh can be fed through extraction or serving. In the extraction case, the monolith produces a dataset or events corresponding to the bounded context of the respective data product. In the serving case, the monolith prepares a data view or events that serve data through a proper connector. Serving is generally preferred to extraction since reduces the need for copying data. Anyway, a compromise between performance, maintenance, organization, and technological opportunities must be taken into account to take the right choice.

Extraction and serving are preparation steps located within the original boundaries of the monolith.

The ownership of those extraction and serving steps should be of the team that manages the data silos.

Extraction and serving apply to both streaming and batch scenarios to address bulk and incremental operations, scheduled or NRT. In streaming scenarios, a data silo serves events whenever the event store resides by that side. For instance, the traditional data platform provides CDC+stream processing+event store to build facades compliant with data products that can subscribe to and consume those events. On the contrary, the extraction occurs if the event store is part of the data product and the traditional data platform uses a CDC to produce ad hoc events for a data product.

Datasets and data views can be seen as facades that can enable the strangler pattern for the data monolith until the same data product can be replaced within the data mesh platform itself.

This is essential to limit the impact of the data integration on the domain teams. Of course, managing such boundaries require governance and should guarantee a certain level of backward compatibility and maintenance.

To regulate the exchange from data monolith to data products, the two parties (domain and data silos organization) should land on a data contract including:

In fact, data schemas must be immutable to guarantee backward compatibility. Also, having the team managing the data silos responsible for data views and datasets dedicated to the data mesh integration should make easier the identification of data incidents.

A schema evolution mechanism is necessary to make the data mesh evolve without having an impact on consumer data products depending on the data product integrated with the external silos.

A further improvement can be the standardization of those ingestion mechanisms. If the need to integrate external data silos with data products is recurrent, the federated governance may detect the opportunity for standardization and require the implementation of standard interfaces to get data from those data silos. This would make those mechanisms available to all data products as self-served internal workloads to leverage the integration.

Input ports can work in push or pull mode depending on the case. It is important for the data product to protect its own data from side effects regardless of the way this data integration happens. That is, pushing data from outside should not imply losing control of the quality provided by the output ports.

Finally, an input port is worth working both internally and externally to the data mesh platform. In fact, it may represent the means to receive data that are necessary to build the data product.

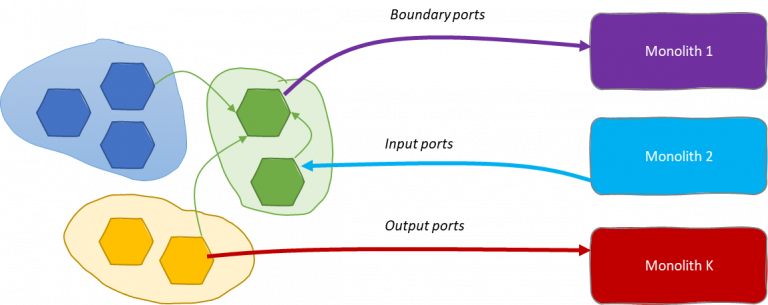

A data mesh may need to coexist with other data monoliths for a long last or forever. This means that the data mesh is not an isolated system and data must be able to flow outbound as well. This is obvious in a transition phase where (for instance) data products built within the data mesh platform must feed preexisting ML systems that still live outside the data mesh.

In this case, we might preserve output ports for the data mesh without wasting their semantics for technical reasons. Instead, we may have some boundary ports that are specifically used to enable this data exchange and deal with external monoliths. A boundary port should not be an input for other data products and the data mesh platform should deny data products consuming from boundary ports.

Boundary ports can serve as input for external data monoliths.

As in the case of analytical monoliths to data mesh, boundary ports may be subjected to standardization by the federated computational governance. The data mesh platform can facilitate those data integration patterns for those cases where the data monolith looks long-standing or cannot be removed at all.

The design of boundary ports can be driven by the technological needs of outside systems. Being technical plugs, boundary ports may leverage the technical capabilities of the data mesh platform to adapt to external data consumption interfaces. The ability to adapt to external systems is key for several reasons. For instance, the agility of the data mesh platform development can enable boundary ports that accelerate the decomposition of those monoliths by facilitating that integration. It would be more difficult chasing legacy system capabilities to speed this process up. This relieves effort from slow-changing organizational units bringing this burden where this can be resolved faster. Finally, keeping this effort close to the data product retains the responsibility of the data quality within the data product.

The integration patterns that we have presented here want to enable agility. Breaking the external monolith may be very cumbersome and costly. There is a need for an incremental and iterative approach to onboard source and consumer data products:

Data mesh—monolith integration patterns can bring agility in the management of the adoption phase.

The integration patterns between a data mesh and the surrounding application and data monoliths can emerge to be necessary in many cases that we are going to explore here. Besides those patterns, it is important to focus on organizational issues most of all in regard to data ownership in the gray areas of the company. Setting ownership of data and processes during a transition or across faded boundaries of an organization is essential to the success of the evolution and maintenance of any initiative. The data mesh is not different in that.

During a data mesh initiative, the cooperation between existing legacy systems, and operational and analytical silos is crucial. Working in bimodality for the period of the adoption is essential to migrate to the data mesh in agility.

Change management is key to success and having solid integration patterns that can assist the evolution can reduce risks and frictions.

A data mesh initiative is realistically rolled out in years from inception to industrialization. The adoption must be agile. It is neither possible nor convenient to invest years in developing a data mesh platform before it is used by the company. This means that a disruptive adoption plan requires all stakeholders to be onboarded at the right pace. Whether you are in the food and beverage, banking and insurance, utility and energy industries, fast-growing data-driven companies must pass through a coarse organization of the adoption and then refine it along the way.

This means identifying first a champion team that can embrace the change at a rapid pace. In parallel, it is necessary to start soon addressing the onboarding of parts of the company relying on application and data monoliths. They require much more time to be embodied and the adoption will face sooner or later the necessity to resolve the data integration problem.

On the one hand, the adoption requires identifying all existing monoliths that will remain forever and determining inbound and outbound permanent data paths to enable analytical scenarios depending on those silos.

On the other hand, the adoption would determine which monoliths must be broken. In this case, the strangler pattern can help us divide and conquer the acquisition of those data assets transforming them into data products.

Another common case in the data mesh path is dealing with M&As of other companies. The data mesh should reduce acquisition risks and accelerate the value chain coming from acquired data assets. This is the promise of the data mesh to ease the business of data-driven companies.

In this scenario, opening data paths between the involved parties can be facilitated through the adoption of integration patterns that assist IT teams from all sides during the transition.

Of course, M&As can reach another degree of complexity given that, even in the case of a mature data mesh, some of the parties could have no familiarity with DDD, data mesh, and any of those concepts posing many organizational and cultural issues to be considered.

In this sense, I would argue that in the case of an M&A there are major issues that need a reconciliation effort between the parties. Data assets and organizational units in charge of operating data will sooner or later meet the necessity to integrate with the existing data mesh. This will also occur for online systems. Having tested integration patterns to rely on can relieve some design effort from the bootstrap. The precedence between online systems and analytical ones will be driven by factors out of the only data mesh doctrine. Anyway, at a certain point, data assets will start moving towards the data mesh platform and solid integration patterns can help break monoliths from all parties.

This article presented the integration patterns between operational and analytical monoliths with a data mesh. It reviewed the Strangler pattern to break data monoliths through the extraction (datasets) and serving (data views) mechanisms governed by data contracts. The boundary ports represent the opportunity to formalize temporary or permanent data paths from the data mesh platform to external data silos. Finally, I've exposed two primary use cases where to apply those integration patterns: data mesh adoption and M&A events to establish temporary and permanent data paths. The advantage of this approach is to keep data ownership as close as possible to the data source, enable integration patterns to facilitate the construction of data products depending on external legacy systems, and have a sustainable path to iteratively and incrementally break data silos that must be embodied within the data mesh.

Data Mesh is completely changing the perspective on how we look at data inside a company. Read what is Data Mesh and how it works.

When it comes to modelling Data Products people go into panic. There are no clear rules, only some conceptual and not actionable indications.

Data Mesh is completely changing the perspective on how we look at data inside a company. Read about what Data Mesh and how it works.